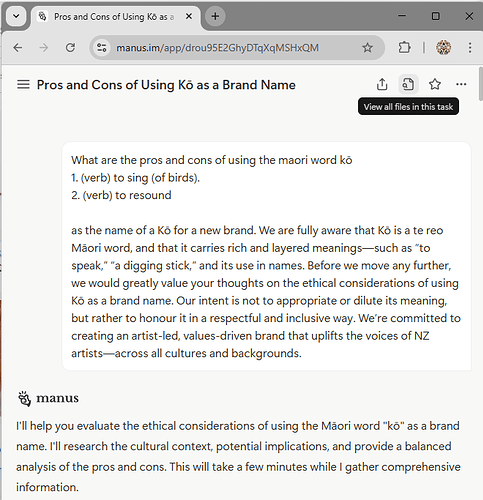

#Manus AI prompt

Manus response

Using the Māori Word “Kō” as a Brand Name:

Ethical Considerations and Recommendations

Executive Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the ethical considerations, cultural implications, and practical recommendations for using the Māori word “kō” as a brand name for an artist-led initiative. The analysis covers the cultural significance of “kō” in Māori traditions, examines case studies of brands that have used Māori terms, evaluates the pros and cons of using “kō” as a brand name, and provides specific recommendations for implementation.

The Māori word “kō” carries multiple meanings, including “to sing (of birds),” “to resound,” and “a digging implement.” These meanings connect to significant cultural concepts and practices in Māori society. Using this term as a brand name requires careful consideration of cultural appropriation concerns, consultation with Māori communities, and implementation of benefit-sharing mechanisms.

This report concludes that using “kō” as a brand name can be ethically appropriate if implemented with genuine respect, proper consultation, clear acknowledgment of the term’s origin, and mechanisms for benefit-sharing with Māori communities. The alignment between the meaning “to sing/resound” and an artist-led brand focused on uplifting voices creates a conceptual foundation that could support ethical use if properly executed.

Table of Contents

-

Introduction

-

Cultural Significance of “Kō” in Māori Traditions

-

Ethical Considerations for Using Indigenous Terms in Branding

-

Case Studies: Brands Using Māori Terms

-

Pros and Cons Analysis

-

Recommendations and Ethical Guidelines

-

Macron Usage Challenges and Regional Conventions

-

Conclusion

-

Appendices

1. Introduction

The question of whether to use the Māori word “kō” as a brand name raises important ethical considerations about cultural appropriation, respect for indigenous knowledge, and the responsibilities that come with borrowing from another culture. This report aims to provide a balanced analysis of these considerations, along with practical recommendations for implementation if you choose to proceed with using “kō” as your brand name.

The analysis recognizes that your brand is artist-led and values-driven, with a mission to uplift the voices of New Zealand artists across all cultures and backgrounds. This context is important in evaluating the appropriateness of using a Māori term as your brand name.

2. Cultural Significance of “Kō” in Māori Traditions

Multiple Meanings

The word “kō” in te reo Māori has several meanings:

-

As a verb: “to sing (of birds)” and “to resound” - these meanings connect to the spiritual significance of birdsong in Māori culture, referred to as “te waha o Tāne” (the voice of Tāne, the forest god)

-

As a noun: A digging implement with both practical and ceremonial significance in Māori agriculture

-

Other meanings: Location markers, particles, and a term for “girl/younger woman”

Cultural Context

The kō as a digging implement was central to traditional Māori agriculture, used for cultivating kumara (sweet potato) and other crops. It held both practical and ceremonial significance, featuring in rituals related to planting and harvesting.

The meaning related to birdsong connects to the spiritual significance of birds in Māori culture. Birds are considered messengers between the human world and the realm of the gods, and their songs carry spiritual significance.

The phonemic nature of Māori language means that vowel length (indicated by the macron in “kō”) is crucial for correct pronunciation and meaning. Incorrect pronunciation can change the meaning entirely or render the word meaningless.

3. Ethical Considerations for Using Indigenous Terms in Branding

Respect for Cultural Heritage

Indigenous terms and concepts are not merely linguistic elements but carry deep cultural, historical, and often spiritual significance. Using these terms in commercial contexts requires acknowledging that they are part of a living cultural heritage that continues to have meaning for indigenous communities today.

Power Dynamics

There is an inherent power imbalance when members of a dominant culture adopt elements from historically marginalized cultures. This imbalance requires extra sensitivity and awareness to avoid perpetuating patterns of exploitation or cultural erasure.

Commodification vs. Appreciation

There is a fine line between cultural appreciation and commodification. Appreciation involves understanding, respecting, and acknowledging the source culture, while commodification reduces cultural elements to marketable assets without proper context or respect.

Consultation and Consent

Ethical use of indigenous terms requires meaningful consultation with and, ideally, consent from relevant indigenous communities or knowledge holders. This is not merely a legal requirement but an ethical principle based on respect for cultural autonomy.

Benefit Sharing

Ethical use of indigenous cultural elements should involve some form of benefit sharing with the source communities, whether through direct partnerships, financial arrangements, or other forms of reciprocity.

New Zealand Context

New Zealand has a unique bicultural foundation based on the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which establishes a partnership between Māori and the Crown. This creates both legal and ethical obligations regarding the use of Māori cultural elements.

4. Case Studies: Brands Using Māori Terms

Problematic Examples

1. Hoka Running Shoes

-

Issue: The French-American company uses the Māori word “hoka” (meaning “to fly”) as its brand name

-

Problem: Initially acknowledged the Māori origin but later removed this attribution after ownership change in 2012

-

Additional concerns:

-

Also uses Māori words for shoe models (Arahi, Hopara) without proper acknowledgment

-

Mispronounces the Māori words in recent marketing materials

-

Some terms like “Arahi” (meaning “to lead”) are considered sacred in certain contexts

-

Lesson: Removing attribution after initially acknowledging cultural origins appears particularly disrespectful

2. Fonterra’s Trademark Attempts

-

Issue: New Zealand dairy company Fonterra attempted to trademark multiple Māori words for cheese products

-

Words involved: Kāpiti, awa (river), kōwhai (yellow), kānuka (white tea tree), kakato (delicious), pakari (firm), kirīmi (cream), akatea (white rātā), kahurangi (blue), kahikatea (white pine), te tihi (summit) and rarama (gleam)

-

Problem: Criticized for attempting to gain exclusive commercial rights to common Māori words

-

Previous controversy: In 2019, Fonterra was criticized for naming its Tuteremoana Cheddar after a Māori ancestor from the Kāpiti area

-

Lesson: Even when attempting to limit trademark scope, claiming commercial rights to indigenous language terms is problematic

3. Air New Zealand’s “Kia Ora” Trademark Attempt

-

Issue: In 2019, Air New Zealand attempted to trademark the logo of “Kia Ora,” the name of its in-flight magazine

-

Problem: “Kia Ora” is a common Māori greeting meaning “good health” and widely used to mean “hello” in New Zealand

-

Reaction: The Māori Council threatened to take the airline to court and called the application “harebrained” and “an insult to New Zealanders”

-

Lesson: Even attempting to trademark stylized versions of common indigenous greetings can be seen as overreaching

More Positive Approaches

1. Whittaker’s Chocolate

-

Approach: Released a special edition chocolate bar with packaging in te reo Māori during Māori Language Week

-

Success factors: Temporary, celebratory use that promoted the language rather than appropriating it

2. Kiwibank

-

Approach: Adjusted their slogan from “Kiwis making Kiwis better off” to remove the incorrect use of the letter ‘S’ (which doesn’t exist in te reo Māori)

-

Success factors: Demonstrated respect for language accuracy and willingness to adapt

3. Companies Using Māori Values Rather Than Just Words

-

Some companies have successfully incorporated Māori values into their business practices:

-

Rangatiratanga (integrity/leadership)

-

Manaakitanga (hospitality/generosity)

-

Kaitiakitanga (guardianship/stewardship of resources)

-

This approach focuses on embodying cultural values rather than simply using language for marketing

Key Lessons from Case Studies

-

Acknowledgment is Essential: Removing or failing to acknowledge the Māori origin of terms is particularly problematic

-

Consultation Makes a Difference: Companies that consult with Māori communities before using terms face less criticism

-

Context and Placement Matter: Using sacred or significant terms in inappropriate contexts can be particularly offensive

-

Legal vs. Ethical Considerations: What is legally permissible may still be ethically problematic

-

Pronunciation and Accuracy: Correct pronunciation is seen as a minimum requirement for respect

-

Temporary vs. Permanent Use: Temporary, celebratory use tends to be better received than permanent appropriation

-

Benefit Sharing: Companies that find ways to share benefits with Māori communities face less criticism

5. Pros and Cons Analysis

Pros

Meaningful Connection to Sound and Voice

-

The meaning “to sing (of birds)” and “to resound” aligns well with an artist-led brand focused on uplifting voices

-

Creates an authentic connection to the concept of artistic expression through sound

-

Offers a rich metaphorical foundation for the brand’s narrative and values

Cultural Richness and Depth

-

Provides access to a term with layered meanings and cultural depth

-

Connects to New Zealand’s unique cultural heritage

-

Offers more substance and authenticity than an invented name

Brevity and Memorability

-

Short, simple, and easy to remember

-

Works well visually in logo design and branding materials

-

Easy to pronounce once proper pronunciation is learned

Potential for Cultural Bridge-Building

-

Could serve as a platform for cultural education and appreciation

-

May create opportunities for meaningful cross-cultural collaboration

-

Could contribute to the visibility and vitality of te reo Māori

Alignment with Brand Values

-

If the brand is truly committed to uplifting NZ artists across all cultures, the name reflects this mission

-

The connection to voice and expression is conceptually strong

-

Could signal the brand’s commitment to New Zealand’s bicultural foundation

Cons

Risk of Cultural Appropriation

-

Without proper consultation and implementation, could be perceived as appropriating Māori culture

-

May face criticism from Māori communities if not handled with appropriate respect

-

Could contribute to a pattern of commercialization of indigenous terms

Pronunciation Challenges

-

Non-Māori speakers may mispronounce the name, potentially causing offense

-

Requires ongoing education of staff, partners, and customers about correct pronunciation

-

Incorrect pronunciation could be seen as disrespectful

Potential for Misunderstanding

-

The multiple meanings of “kō” could lead to confusion about the brand’s focus

-

Some may associate it primarily with the digging implement meaning rather than the sound-related meanings

-

International audiences may not understand the cultural context

Additional Responsibilities

-

Creates obligations for ongoing consultation and relationship-building with Māori communities

-

Requires commitment to cultural education and proper acknowledgment

-

May necessitate benefit-sharing mechanisms that affect business operations

Potential Backlash

-

Could face criticism from both Māori and non-Māori perspectives

-

May become subject to changing standards of cultural appropriateness

-

Could be affected by broader social and political discussions about indigenous rights

Summary Assessment

The use of “kō” as a brand name presents both significant opportunities and serious responsibilities. The alignment between the word’s meaning related to sound/voice and an artist-focused brand creates a strong conceptual foundation. However, this opportunity comes with the responsibility to engage respectfully with Māori culture and communities.

The decision ultimately depends on the brand’s willingness and ability to:

-

Engage in meaningful consultation with Māori language experts and cultural advisors

-

Properly acknowledge and educate about the term’s origin and meaning

-

Ensure correct pronunciation and usage in all brand communications

-

Develop mechanisms for benefit-sharing with Māori communities

-

Maintain ongoing relationships with Māori advisors or partners

6. Recommendations and Ethical Guidelines

Key Recommendations

1. Consultation Process

Recommendation: Engage in meaningful consultation with Māori language experts, cultural advisors, and if possible, representatives from iwi (tribes).

Implementation Steps:

-

Reach out to organizations such as Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori (Māori Language Commission)

-

Consider engaging a Māori cultural consultant with expertise in business and branding

-

Approach local iwi representatives, particularly those with traditional connections to your region

-

Document the consultation process and incorporate feedback into your brand development

2. Cultural Acknowledgment

Recommendation: Clearly acknowledge the Māori origin and meaning of “kō” in your brand materials and communications.

Implementation Steps:

-

Include information about the meaning and origin of “kō” on your website and in brand materials

-

Explain which specific meaning of “kō” (to sing of birds, to resound) your brand connects with

-

Provide context about the cultural significance of this meaning in Māori culture

-

Avoid presenting the term as merely an interesting or exotic word

3. Pronunciation and Usage

Recommendation: Ensure correct pronunciation and usage of “kō” throughout all brand communications.

Implementation Steps:

-

Include pronunciation guides in brand materials (the macron over the ‘o’ indicates a long vowel sound)

-

Train all staff, especially customer-facing employees, in correct pronunciation

-

Include audio pronunciation on your website

-

Be consistent in the use of the macron (ō) in all written materials

4. Benefit Sharing

Recommendation: Develop mechanisms for sharing benefits with Māori communities or supporting Māori cultural initiatives.

Implementation Steps:

-

Consider allocating a percentage of profits to Māori cultural or language initiatives

-

Create opportunities for Māori artists within your brand ecosystem

-

Support Māori-led events or programs related to arts and culture

-

Establish scholarships or mentoring programs for emerging Māori artists

5. Ongoing Relationship

Recommendation: Maintain ongoing relationships with Māori advisors or partners rather than treating consultation as a one-time event.

Implementation Steps:

-

Consider establishing a cultural advisory board that includes Māori representation

-

Schedule regular check-ins with cultural advisors to review brand activities

-

Be open to evolving your approach based on feedback

-

Participate in cultural education opportunities to deepen your understanding

Ethical Guidelines for Implementation

Authenticity and Alignment

-

Ensure your brand’s values and activities genuinely align with the meaning of “kō” you are drawing upon

-

Be prepared to adapt your business practices to maintain this alignment

-

Avoid using “kō” merely as an exotic or trendy element disconnected from its meaning